|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 48 Number 22, November 11, 2018 | ARCHIVE | HOME | JBCENTRE | SUBSCRIBE |

Workers' Weekly Internet Edition: Article Index : ShareThis

Commemorating the Centenary of the End of the First World War

World War I - An Inter-Imperialist War

British Imperialism and the First World War

World War I and the Fight of the Working Class for Peace and an Anti-War Government

Criminal Role of Social Democracy in the First World War

Massive Conscription of Indians by the British

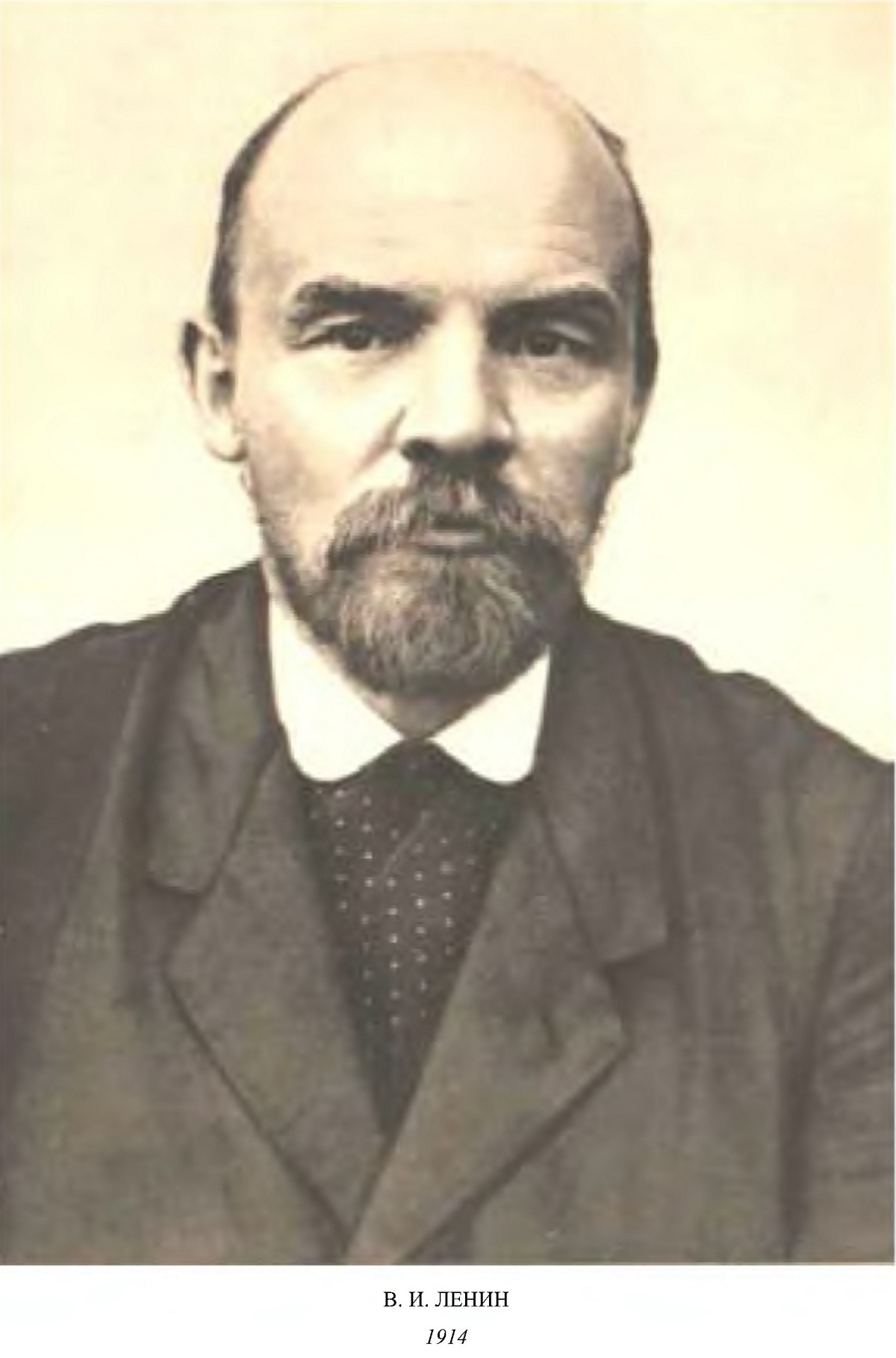

Appeal to the Soldiers of All the Belligerent Countries - V.I. Lenin

May Day demonstration in Scotland in 1917

Sunday, November 11, marked Remembrance Day, the centenary of the signing of the Armistice which brought World War One to an end. The subsequent peace treaties, as is well known, were a factor in laying the grounds for the growth of fascism and World War Two. The First World War was an inter-imperialist war, a war in which working men were sent to the slaughter as empires clashed to redivide the world. The high ideals of a War to End All Wars, of duty to king and country, to empire, were shown to be a cover, a false justification, for this horrendous clash of the imperialist warmongers. Yet these same values are promoted under the rubric of "Lest we forget", that the dead are the glorious ones, because they made the supreme sacrifice. In Britain, the two world wars are being equated as both being fought for freedom against a heinous enemy.

But such an interpretation is not being unchallenged. While the big powers, including Britain, are utilising the occasion to speak of international security while preparing for war and stepping up military spending and the arms industries, the masses of the people are affirming that the truth must be told, that they must organise themselves for peace. They are affirming that people from all walks of life are refusing to glorify this slaughter, that this occasion is one for speaking the truth, for releasing the initiative of the people as the force for peace, that they view the fight for peace from a different vantage point than the hypocrisy and double-dealing of those that head pro-war governments of the day.

The working class and people will not forget the nature of inter-imperialist war, and based on their experience will organise to take their fate into their own hands. If sacrifices are to be made, they will be made to bring into being a society which is profoundly democratic and will indeed put an end to war.

Mass protest on International Women's Day, 1917 in

Russia, demanding peace, land and bread

On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, one hundred years passed since the fighting in World War I ended, following the signing of an armistice between, Britain, the Allies and Germany.

World War I was a slaughter of unprecedented proportions. The total number of military and civilian casualties is estimated to have been about 40 million people - 15 to 19 million deaths and about 23 million wounded military personnel. The deaths include some 8 million civilians, of whom 6 million are estimated to have died of war-related famine and disease - such as the 1918 flu pandemic, and the deaths of prisoners of war. From Britain alone, nearly 750,000 combatants had lost their lives, 54,000 were classified as "missing", presumed dead, and 1,500,000 had been disabled.

World War I lasted from 1914 to 1918. It is said to have started on July 28, 1914, when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Russia soon followed, declaring war on Austria-Hungary, and within six days, Britain and France were officially at war with Germany. In addition, large parts of the colonial empires of the belligerent countries in Africa, Asia and elsewhere, some 4,000,000 were automatically at war too, since the war was a truly global conflict and military engagements took place in Africa and Asia, including the so-called Middle East, while troops from Africa and Asia also fought in Europe. From Germany's African colonies 200,000 porters were conscripted, from France's African colonies 450,000 soldiers. In East Africa alone it is estimated that 1,000,000 lost their lives.

Japan participated in World War I from 1914 to 1918 in an alliance with Entente Powers. In this period, Japanese imperialism was also occupying the Korean Peninsula. The Japanese empire seized the opportunity to also expand its sphere of influence in China, and seized German possessions in the Pacific and East Asia

British soldiers on the Somme, July 1916

The terrible conflict between the combatant countries tore asunder the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and German Empires. The end of the war did not end the greed of the power-hungry men who started it in the first place. British troops were deployed to crush Ireland's struggle for independence, giving the lie to its hyperbole of participating in the war to defend the independence of "gallant little Belgium", itself a kingdom which brutally ruled colonies in Africa. British troops, along with troops from ten other countries, at the instigation of Britain and France, were sent to invade Russia following the 1917 revolution, in a vain attempt to maintain the privileges of the Tsarist regime negated by the establishment of the world's first socialist state.

There continues to be massive disinformation about the causes and nature of World War I. In 2014, leading government ministers even claimed that it was fought to defend "western civilisation" and the independence of Belgian or to end "warmongering and imperial aggression". In fact the war broke out because of the warmongering and imperial aggression of Britain and the other big powers.

The First World War was a slaughterhouse of unprecedented proportions. It also marked a turning point in history. In the aftermath of the war, drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change occurred in Europe, Asia and Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. As four empires collapsed due to the war - the Russian Tsarist Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire - old countries were abolished, new ones were formed and boundaries were redrawn. International organizations such as the League of Nations were established.

A profound anti-communist outlook began to take hold in Europe and North America in light of the New being built by the working class in Soviet Russia which defeated Tsarism in the Great October Socialist Revolution of 1917, led by the Bolshevik Party and its leader V.I. Lenin, and embarked on an entirely new nation-building project where power was placed in the hands of the soviets of workers, peasants and soldiers.

Far from being the war to end all wars, World War I perpetuated the colonial system, denied nations the right to self-determination and sowed the seeds of future conflicts and wars in Europe and globally. A hundred years later, the economic and military contention between the big powers is again only too evident.

World War I was an inter-imperialist war for the redivision of the world. Then, as today, the events which led up to World War I show the workers of all countries that unless they establish anti-war governments it is in fact slaughter that awaits them.

Gassed by John Singer Sargent

To this day the conflict which led to World War I continues to be presented as a noble and just cause. One of the main arguments advanced at the time Britain declared war on Germany was a duty to defend the right of self-determination of small countries, Britain's stranglehold over Ireland notwithstanding. To this day, official circles continue to assert that the British government declared war in response to Germany's invasion of Belgium and therefore "in defence of international law and a small state faced with aggression". Some go even further declaring that the government of the day acted to end "warmongering and imperial aggression" . No attempt is made to look at the underlying causes of the war, which include the "warmongering and imperial aggression" of all the big powers, including Britain.

Map of borders and empires in Europe before World War

I

By 1900 the world had been almost completely divided between the big powers that had staked out colonial territories and spheres of influence. Nevertheless, contention continued with all the major powers seeking re-division of the world in order to gain an advantage over their rivals.

For instance, Britain's "entente" with France was a consequence of its evident international isolation following earlier imperial aggression in South Africa. Britain's alliance with France then led that government to threaten Germany with war when the latter squabbled with France over which power should invade and occupy Morocco. It is clear that in this case Britain did not defend the sovereignty of a small state faced with aggression. It was content to support France's aggression against their common rival Germany, because France had agreed to accept Britain's prior invasion and occupation of Egypt.

British imperialism chose to use Belgian "neutrality" as a justification for war against its rival Germany but did not seek to prevent the aggression of the Belgian monarch, Leopold, against the people of the Congo. In the 30 years preceding the First World War, Belgian imperial aggression led to the deaths of some 10 million Africans, probably half the Congolese population, without any intervention by any of the big powers. This is not surprising because all the major powers fought wars of aggression and conquest not only in Africa and Asia but wherever their predatory interests led them. In this regard, Britain was the most aggressive and predatory of all the big powers at that time.

The British government's warmongering and imperial aggression was also expressed in the rapid expansion of its navy and the secret naval agreement with France in 1912, both of which were directed against Germany. A new alliance with Russia in 1907, which opened a new chapter in what was then known as the "great game" of Anglo-Russian contention in Central Asia, was based on a joint agreement that denied Afghanistan and Persia their sovereignty and placed the resources of these countries at the disposal of banks and monopolies of Russia and Britain. Such alliances were clearly undertaken in the context of British imperialism's predatory interests and in contention with Germany, its main rival at the time.

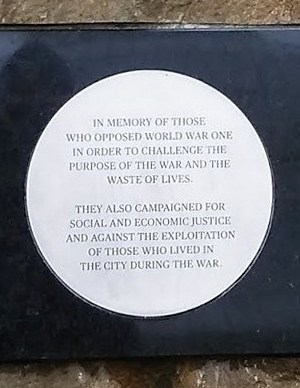

Plaques to conscientious objectors in Tavistock Square,

London

The division and redivision of the world not only precipitated war and created the conditions for the international alliances that turned Europe into two camps of armed robbers. Secret negotiations and treaties during the war sanctioned further re-division. In 1915, the British government reached a new secret agreement with Russia over the division of Persia, that decided it would fall into Britain's hands, while Russia was compensated with rights to parts of the Ottoman Empire, including its capital Constantinople; and Britain and France would acquire other Ottoman territory. When Italy joined the Allied powers, the British government entered into a secret treaty partitioning the Austro-Hungarian Empire, allowing Italy to seize further territory in Africa, including Libya and in the Horn of Africa, thus violating the sovereignty of the Libyan, Somali and other peoples in that continent. Secret plans were also made for the dismemberment of Ethiopia. These secret agreements paved the way for France to annex Syria and Lebanon, and Britain would take what is today Iraq. The secret treaties paved the way for the British government's Zionist occupation of Palestine, which to this day denies the Palestinian people their right to be.

Significant opposition existed to the "Great War" throughout Britain, and not only amongst workers and peace-loving people in Britain but also throughout the empire. In Africa, for example, large-scale rebellions against forced conscription and other aspects of colonial rule were widespread. In what is today Malawi, for example, John Chilembwe led an armed uprising against colonial rule after warning the colonial authorities: "I hear that, war has broken out between you and other nations, only whitemen, I request, therefore, not to recruit more of my countrymen, my brothers who do not know the cause of your fight, who indeed, have nothing to do with it ... It is better to recruit white planters, traders, missionaries and other white settlers in the country, who are, indeed, of much value and who also know the cause of this war and have something to do with it." The rebellion was viciously suppressed and Chilembwe and other leaders executed.

John Chilembwe, Baptist church minister, pictured on

left

In Britain, the Jamaican conscientious objector Isaac Hall refused to be conscripted declaring: "I am a negro of the African race, born in Jamaica ... My country is divided up among the European Powers (now fighting against each other) who in turn have oppressed and tyrannised over my fellow-men. The allies of Great Britain, i.e. Portugal and Belgium, have been among the worst oppressors, and now that Belgium is invaded I am about to be compelled to defend her... In view of these circumstances, and also the fact that I have a moral objection to all wars, I would sacrifice my rights rather than fight." Hall was tortured and incarcerated in Pentonville Prison for two years but refused to renounce his principles.

The notion that the British government entered the First World War to uphold "civilised values" or for a "just cause" or to defend the rights of small nations is a dangerous fiction that has no basis in fact. It is disinformation advanced to deprive the people of an outlook which is required to give rise to an anti-war government today. The conditions for the First World War grew out of the conditions of the imperialist system of states at that time, not least the intense rivalry between the big powers for markets, raw materials and spheres of influence, which they sought to secure through a violent re-division of the world.

The 100th anniversary of the end of World War I is an occasion to draw warranted conclusions from the experience of the working class and people before, during and after the war.

Protest by conscientious objectors in Dartmoor in

1917

When the guns fell silent on November 11, 1918, one hundred years ago the world had gone through the most traumatic event in its history which was then called the "Great War" and later to become known as the First World War which had killed millions of people world-wide. If we look today for the role of the British working class in the First World War we are presented only with the suffering of the hundreds of thousands of workers killed and injured in the war with only the humanity and suffering passed down to us by the wonderful poetry writings and art of Wilfred Owen and others. Even the stories of the heroic fight of the conscientious objectors is not well known. The speeches of the ruling elite today continue to distort the predatory imperialist nature of the conflict, waged by Britain and the other big powers to re-divide the world, but also to hide the fact that there was sustained opposition to the war and its consequences, not only in Britain but also in many other countries, in which the working class played a leading role both at home and in the colonies.

Workers' Opposition

In fact, the British working class and the peoples of Britain's colonies were in opposition to the war from the outset and wanted to be free from exploitation and oppression and wanted to be in control of their own nations and to live in peace. Prior to the war huge struggles of hundreds of thousands of workers had broken out. From 1910 to 1914 the dockers, engineering workers, railway workers and miners launched huge strike struggles in what was described at the time as the "General Spirit of Revolt" against the low wages and terrible conditions that workers faced. The historic year of 1913 witnessed the General Strike in Dublin in August and September. The Irish Transport and General Workers Union was under the leadership of James Connolly and Jim Larkin. This fierce struggle of 80,000 Dublin workers aroused an extraordinary response. Solidarity was symbolised in the enthusiastic dispatch through the Co-operative Movement of a food ship to Dublin, and in the sympathetic strikes in which some 7,000 British railwaymen took part. There was a wave of unlimited police terror launched against the Dublin strikers. Two workers were killed, 400 wounded and over 200 were arrested. There was outrage and talk of arming the workers, general strikes and revolutionary action throughout the trade unions.

John Maclean's speech from the dock at his trial for

sedition, May 9, 1918

The summer of 1914 was working up towards an outburst of gigantic workers' struggles for their rights. The miners were preparing new autumn claims. The transport workers were organising and railwaymen and engineers were preparing. In 1914 an alliance for mutual aid was proposed and agreed between the Miners Federation, the National Union of Railwaymen and the Transport Workers Federation. This was to be called the Triple Alliance. The ruling class were in a deep crisis; the problems in Ireland and the internal situation were grave. The English aristocrats, Tory politicians and army officers were preparing for civil war. Lloyd George said openly that with labour "insurrection" and the Irish crisis coinciding, "the situation will be the gravest with which any government has had to deal for centuries". They thought that if the war did not materialise quickly it could be forestalled by the workers seizing power themselves and demanding peace. For the British ruling class, bringing forward the launching of the inter-imperialist war to seize colonies off their rivals in Africa and Asia was imperative to divert the interests of the workers to pursue their war in rivalry with Germany.

However, as soon as the war was declared at this time, the working class of Britain, Germany and France suffered their worst blow from those labour and trade union leaders who declared their support for the war, saying to workers that they should discard their own interests and those of peace, and fight for "defence of the fatherland". These leaders directly assisted the government with its aim to crush the workers' struggles, declare strikes and other trade union activities illegal in many industries for the duration of the war, and for the introduction of the draconian Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), which made active opposition to the war a criminal offence. In 1915, leading members of the Labour Party joined the warmongering coalition government. European socialist parties of the Second International had sunk to the ignominious level of supporting their own imperialist powers in the slaughter of the First World War.

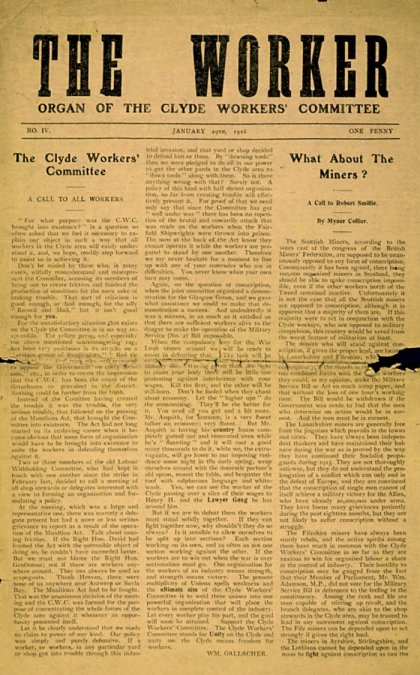

Issue of The Worker, January 29, 1916, newspaper of the

Clyde Workers' Committee

In Britain, opposition to the war and the government's policy of forced conscription was widespread. This was seen with the brave stand of the working class and people against the war. There were 16,000 officially declared "conscientious objectors", who refused to join the armed forces on principle and several thousand of them were imprisoned for their stand.

Also, the working class including the women, who were drafted into the war industries and munitions factories, defied the trade union leaders who supported the war machine and built their own shop stewards committees and transformed themselves into workers' representatives and leaders against the war and its attacks on the workers. Strikes took place during the war against the wishes of the union executives. In 1915 on Clydeside, shop stewards in engineering led the action of 10,000 workers for a pay increase and 15 establishments were involved, including large armament firms, and overtime ceased on war contracts. A ballot on March 9 led to shops coming out on strike. Local shop stewards organised what became the Clyde Workers' Committee, with hundreds of delegates elected directly from the workplace meeting on a weekly basis. Thousands of workers in South Wales also took strike action against repressive government legislation aimed at curtailing their rights The government intervened under the Munitions Act but 200,000 miners struck and in less than one week the government turned about, over-rode the coal owners, and conceded the main points at issue.

The Irish workers had raised the slogan, "We serve neither King nor Kaiser, but Ireland." In 1916, the heroic Easter Rising took place in Dublin led by James Connolly and other Irish leaders for Irish independence against British colonial occupation from which thousands of Irish workers had been led to their slaughter in France. Even though the rising was suppressed and their leaders murdered by the British state, the Rising was an heroic blow against the British warmongering state and changed the face of Ireland for ever.

Citizen Army banner at Liberty Hall, Dublin, declaring

"We serve neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland"

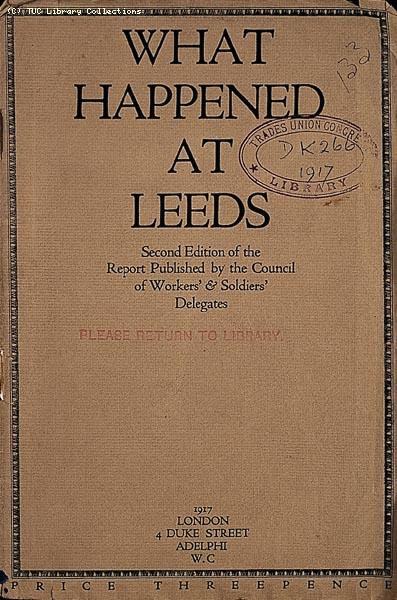

In 1917, engineering workers throughout Britain went on strike in opposition to government plans for more widespread military service and other anti-worker measures. In fact the Russian Revolution which was developing at that time in the overthrow of the Tsar in February which showed the prominence to the Soviets of workers and soldiers in that revolution had a politicising effect on the British working class in opposing the war. This was reflected in the Leeds Convention of June 3, which was attended by 1,150 delegates for the setting up of a Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Delegates. Amongst the calls at the convention were appeals for a struggle against the war. With the completion of the October Revolution in Russia and Russia's withdrawal from the war very large mass scale struggles broke out in the army against the war in the British, French and German armies amongst the soldiers and sailors, armies in which thousands of soldiers had been drafted from the colonies.

At Étaples and Boulogne, between September and December 1917, demonstrations and strikes by troops in protest at their appalling mistreatment by the military commanders resulted in scores of Chinese and Egyptian soldiers in the British Expeditionary Forces being shot and wounded after they refused to work and tried to break out of camp.

There was widespread opposition to the war when rebellion erupted in 1918 when a total of 676 troops were officially court-martialled and sentenced to death for acts of "sedition and mutiny". Though not all these death sentences were carried out, unofficially many other rebellious soldiers were summarily shot on the spot.

The first of the big mutinies on the British mainland occurred in early 1918 when machine-gunners in the Guards staged a mass strike at Pirbright in Sussex. For three days, all soldiers refused duty and instead organised their own voluntary training sessions.

At the end of the year, the spate of rebellions accelerated. On November 13, there was mutiny at Shoreham when troops marched out of base camp in protest at brutality and degrading treatment by their officers. They won. The army responded by demobbing a thousand soldiers the following morning and another thousand each week thereafter.

Leeds Convention to end the war and establish workers'

and soldiers' councils

Among overseas troops, the fervour of dissent was equally pronounced. At Le Havre, Royal Artillery units rioted on December 9, 1918, burning down several army depots in the course of the night. The most sustained mutiny by troops took place at army camps surrounding Calais. Unrest within the units stationed there had been building up for several months beforehand over issues such as cruel and humiliating punishments, the censorship of news from home, and bad working conditions in the Valdelièvre workshops.

There was also discontent over the savage ten-year sentences imposed on five teenage soldiers for relatively minor breaches of discipline, and the harsh regime in Les Attaques military prison, where detained soldiers were flogged and manacled for trivial offences such as talking to each other and were only issued with a single blanket, even during the severest of winters.

Previously, on August 2, 1917, when British troops took up their new positions at Ypres, rebellion broke out on the German battleship Prinzregent Luitpold at the port of Wilhelmshaven. At that point a stoker, Albin Kobis, led four hundred sailors into the town and addressed them with the call: "Down with the war! We no longer want to fight this war!" After returning to the ship some 75 of them were arrested and imprisoned and the leaders were subsequently tried, convicted and executed. "I die with a curse on the German-militarist state," Albin Kobis wrote to his parents before he was shot by an army firing squad at Cologne. He is now remembered as an anti-war hero of the German working class and people.

On October 28, tens of thousands of sailors in the German High Seas Fleet steadfastly refused to obey an order from the German Admiralty to go to sea to launch one final attack on the British navy. By October 30, the resistance had engulfed the German naval base at Kiel, where sailors and industrial workers alike took part in opposing the war; within a week, it had spread across the country, with revolts in Hamburg, Bremen and Lubeck on November 4 and 5 and in Munich two days later. This time the Kaiser's government collapsed setting in motion a course of events that culminated with the Kaiser's abdication and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic in Berlin on November 9, and the signing of the Armistice two days later on November 11, 1918. Far from the victory that that British and its allied powers claimed, this whole catastrophic and unprecedented world war had been brought to an end by the working class and people and their heroic struggles worldwide for peace. However, the struggle of the workers against war were not over. Following the war, attempts took place to by Britain, Germany, Poland and others powers to invade the new Soviet Union to crush the new socialist state. It was in no small part due to the the British workers and the Hands off Russia Committees that Britain intervention in Russia failed and they failed to crush the first new anti-war government.

Imprisonment

As recounted on the website of the Peace Pledge Union, "The Men Who Said No", many conscientious objectors (COs) ended up in prison. For some, this was a conscious choice made at the start of conscription to refuse participation in any activity they felt would contribute to the British war effort, whether in the Non-Combatant Corps or in the various Home Office Schemes. They were known as the Absolutists. For others, imprisonment was the ultimate destination they reached as their thinking developed and they considered what stand to take to be effective in opposing the war and conscription. Still others were imprisoned because the army had violated their right to participate in the military in non-combat roles and they had been court-martialled for refusing orders.

The Wakefield Experiment was one of the last, and shortest-lived, attempts made by the government to encourage Absolutist COs to compromise on their principles. It underscored the harsh treatment of the COs and the violation of their rights, and the unjust nature of Britain's participation in the war as a whole.

The Wakefield Experiment was devised to prolong the imprisonment of COs, and rapidly became a political embarrassment for the government as the war wound to a close. It had been planned as a way to involve COs in their own punishment, allowing them to essentially manage their conditions in prison, and therefore keep them locked up without significant protest until the government saw fit to release them. Though a significant compromise on the part of the government, its purpose was merely to be a stop-gap measure intended to mollify many of the concerns and protests that had built up over the past two years.

A group of Conscientious Objectors leaving Dartmoor

Prison

After a period of settling in, the Wakefield men had taken it upon themselves to organise and run the prison as they wished. Committees divided the labour of prison upkeep and cordially invited the wardens to help if they wished. The Governor, with no instructions on what to do, allowed the Chairman of the Committee, Walter Ayles, to represent the official Home Office plan for the prison to the assembled men. Ayles presented the rules and regulations on how COs in Wakefield would be expected to work and live on September 16. There had been no great threat of exceptional mass punishment, simply that if the rules of the new scheme were not followed, men would be returned to prison. The position was simple. In exchange for their work, COs would stay in Wakefield and be managed, in all essential respects, by themselves.

Two days later, with a resounding rejection of the principle of compromising conscience for better conditions, all but six of the 125 COs were back in locked cells, soon to be returned to the prisons they came from.

The final piece was the creation of the "Manifesto of the Absolutists

at Wakefield." Not only had the COs held there organised and discussed

their thoughts, but had formed a committee which wrote, drafted and distributed

a clear statement of intent. The Manifesto signalled the clearest statement of

the Absolutist

Plaques to conscientious objectors in

Glasgowposition. Despite better conditions, no manner of

compromise would fulfil the aim of the Absolutists: unconditional liberty and

discharge from the army. The Manifesto explained that the government "take

for granted that any safe or easy conditions can meet the imperative demands of

our conscience. No offer of schemes or concessions can do this. We stand for

the inviolable rights of conscience in the affairs of life."

The 123 men at Wakefield refused any form of compromise with the government and demanded either release, or a return to prison. No change in their circumstances could win them over and put them to work.

The position outlined in the Manifesto had been the Absolutist stance since before conscription had become law, and the rejection of the Wakefield Experiment was the last attempt by the government to subvert or undermine it. The Wakefield men returned to prison, and the incarceration of COs continued as before.

Conclusion

The experience of the First World War showed that the workers of Britain and other countries must play a leading role in society to stop the war. The betrayal by the Labour Party and other parties which comprised the Second International showed that the workers must organise themselves based on their own independent programme and aims. They must give up illusions that electoral parties which comprise party governments in the service of the bourgeoisie will serve their interests.

Today, the workers must organise with the perspective of creating their own anti-war government, building the proletarian front to bring this about, and settling scores with all pretexts for the betrayal of their interests.

Chris Coleman

Stuttgart Congress of the Second International,

1907

The treachery of the social-democratic parties which comprised the Second International was, in the words of one commentator, "the worst debacle ever sustained by the world's working class in its entire history".[1] In the quest to lead the working class to constitute the nation today and fight for anti-war governments, the experience of the international workers' movement in defeating the social chauvinism of the Second International has important lessons.

For nigh on 25 years, beginning at the Brussels conference of 1891, the Second International had been passing resolutions warning of the war threat and calling for opposition to inter-imperialist war. The London conference of 1896 had even called for the abolition of standing armies, arming the people, arbitration courts and war referendums by the people. At the Stuttgart Conference of 1907 the famous resolution was passed, its concluding paragraph drafted by V.I. Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, the principles of which remain valid to this day. It read:

If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working class and of its parliamentary representatives in the country involved, supported by the consolidating activity of the International (Socialist) Bureau, to exert every effort to prevent the outbreak of war by means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the accentuation of the class struggle and of the general political situation.

Should war break out nonetheless, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and to do all in their power to utilise the economic and political crisis caused by the war to rouse the peoples and thereby hasten the abolition of capitalist class rule.[2]

There is little doubt that the social democratic parties could have prevented the war or at least brought about its speedy termination. In a situation of mass opposition to war throughout Europe, the most powerful of the parties of the Second International, the German Social Democrats, were in a position to do so, and moreover, even to lead a revolution. Only the Russian Bolsheviks, however, of those in any position to do so, remained true to the principles agreed at Stuttgart. And it was to be the October Revolution, led by them, which brought the terrible destruction of the war to an end. But as the dark clouds of war gathered and every imperialist power found justification and saw opportunity to advance its interests - Germany to seize colonies from Britain and France and the Ukraine, the Baltic provinces and Poland from Russia; tsarist Russia to partition Turkey and seize Constantinople and the straits to the Mediterranean; Britain to smash its rival Germany and seize Mesopotamia and Palestine from Turkey; France to seize the Saar and Alsace-Lorraine from Germany; and the USA in the background ready to exploit any opportunity to advance its ambition for world mastery - party after party of social democracy took up the capitalist's banner of national chauvinism and supported war. Only the Russian and Serbian parties in the Second International resisted.

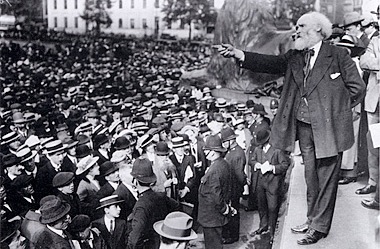

Independent Labour Party MP James Keir Hardie speaking in

Trafalgar Square August 3, 1914, opposing the outbreak of war

Decisively, the German Social Democrats were among the first to move, voting for war credits in the Reichstag. In Britain, typically, the social democrats were more circumspect. The mass of the working class in Britain, as in other countries, was bitterly opposed to the war which broke out in August 1914. The Labour Party responded to this sentiment by calling demonstrations throughout the country on the eve of Britain's entry. The British section of the International Socialist Bureau issued an anti-war manifesto, signed by Arthur Henderson and James Keir Hardie, which ended with the slogans "Down with Class Rule", "Down with War". These two were chief speakers at an enormous Trafalgar Square rally, the biggest ever known, where resolutions were passed calling upon the organisations of the workers to keep to the resolutions of the Second International against imperialist war. Other huge demonstrations took place across the country.

However, the Labour Party leaders ensured things did not go beyond demonstrations and fine words. In the very first days of August the Daily Citizen, organ of the Trades Union Congress and Labour Party, called on the workers to "stand together in defence of the Motherland". Within weeks the trade unions signed a pact of "civil peace" with the Liberal Government, the Labour Party entering into a similar pact in the political field. The Independent Labour Party (ILP), whose leaders including Ramsay Macdonald were also leaders of the Labour Party, issued "Down with the War" manifestos, but these were confined to demands for "peace" and calling on the workers to do "general propaganda for socialism, though not dealing specifically with the war". Meanwhile rank-and-file militants of the ILP and British Socialist Party were encouraged to take up pacifism and conscientious objection, subject to the brutal criminalisation of conscience by the British elite.

Lenin's work "The Collapse of the Second

International" from the Red Clyde collection

By the end of August the National Labour Party executive and the Parliamentary Labour Party, which included five ILP members, had accepted an invitation from the Government to join the recruiting campaign. Such treachery was closely followed by an agreement between Henderson and Prime Minister Lloyd George which prohibited strikes and adopted compulsory arbitration for any disputes in munitions production. This agreement led to the draconian Munitions Act of June 1915, which enforced compulsory arbitration throughout industry and controlled the employment and movement of all workers. Local Munitions Tribunals, including trade union officials, enforced its strictures. By early 1916, when compulsory conscription was introduced, Labour Party leaders were part of the Government and had ceased any form of opposition to the war.[3]

"Defence of the rights of small nations" was one of the pretexts of the British government for entry into the war. But when the Irish rose on Easter 1916 and declared the Republic, the uprising was crushed with great brutality, mass executions and other atrocities. Labour leaders, now Ministers in the government, were complicit in this. The ILP in their journal Labour Leader declared that they "condemn as strongly as anyone those immediately responsible for the revolt" and said that James Connolly, cruelly murdered by the British while critically wounded, was "terribly and criminally mistaken".[4]

Support for the inter-imperialist war by the social democrats, however, was only the beginning of the great betrayal. Despite the dreadful slaughter and destruction of the war, it opened up great opportunities for the advance of the people's cause. Four great Empires had been destroyed - the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman. New independent nations came into existence. Revolutionary upheavals with a distinct anti-capitalist socialist character swept Europe. But only the Bolsheviks in Russia were to seize the opportunity. Elsewhere the treachery of social democracy was to be the main factor in revolution and socialism not prevailing in most if not all the area involved.

In Germany itself revolution broke out in November 1918, sparked by the Kiel mutiny in the German Navy. Revolt spread like wildfire and, influenced by the Bolshevik example, Soviets were established all over the country. On November 9 the national government collapsed and the Kaiser fled. With leadership, the German working class was in a position to push through the proletarian socialist revolution. The Social Democratic leadership had no such intention. They did not want or believe in socialism. They were liberals, who only strove to patch up capitalism a bit here and there. Their leader, Ebert, had said: "I hate revolution as I hate sin."[5] In close co-operation with the capitalists "to save Germany from Bolshevism", they set up first a caretaker government headed by Ebert, then a Provisional Government of Social Democrats and Independents. They manipulated the German Soviet's Congress to support the Provisional Government, then provoked armed struggle with the Spartacists and set reactionary military elements against the fighting workers. Berlin's streets ran with blood and the rebellion was crushed. In the course of this Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were arrested and murdered.

Within weeks the bourgeois Weimar republic was set up, with the capitalists cynically putting right-wing Social Democrats at the head of the government - Ebert himself, Scheidemann and Noske. Even the Soviets were given "advisory" capacity! It was this government, headed by Social Democrats, that signed the Versailles Treaty which was inevitably to pave the way for the rise of fascism and the horrors of the next world war.

By the end of World War I, a revolutionary situation had developed in Britain too. Unofficial strikes had become widespread. The Shop Stewards Movement, severed from "official" Labour, grew in influence. In Scotland, the revolutionary Clyde Workers Committee, despite all attempts to crush it - including the repeated jailing and brutal mistreatment of its political leader, the teacher John MacLean - had made laws regulating employment and conscription inoperable on the Clyde, among other victories. A huge movement had developed against the war. Mutinies spread in the Army and Navy - notably the burning of the base at Étaples by mutineers.[6] Even the police had formed a union and were striking. Mass support for the Bolsheviks was recorded among the militant workers and when the government sent troops to intervene in the new Soviet state, disaffection among the soldiers and sailors was a major factor in bringing the intervention to a sorry end. When again the government sought to intervene in support of the Polish White Guard invasion of Soviet Russia in Spring 1920, mass action in opposition took place throughout the country. The munitions ship Jolly George, bound for Poland, was famously rendered unsailable by the dockers on the Thames. "Councils of Action" were set up by workers across the country. Lenin himself likened the situation in Britain to that in Russia at the time of the February Revolution of 1917, saying that the Councils of Action were in essence Soviets, and pointing out that even the opportunist social democrats had been forced to support them.

Once again, however, these same social democrats were to rescue the bourgeoisie. Vicious anti-Soviet propaganda and attacks on the revolutionary workers, as well as on the newly formed Communist Party, rapidly became the official policy of the Labour Party and ILP. This treachery, combined with the heritage of opportunism even among the best elements of the working class, and the relative weakness and frequent sectarianism of the communists, meant that the bourgeoisie survived the revolutionary crisis of 1919-20 in Britain.[7]

The key role of the opportunist social democrats in preventing socialist revolution and keeping the capitalists and imperialists in power in all but Russia, when the opportunity had so vividly presented itself during the First World War period, was summed up brilliantly by Lenin at the Second Congress of the new Communist International (the Third International) in 1920. He famously said in his report:

Practice has shown that the active people in the working class movement who adhere to the opportunist trend are better defenders of the bourgeoisie, than the bourgeoisie itself. Without their leadership of the workers, the bourgeoisie could not have remained in power. This is not only proved by the history of the Kerensky regime in Russia; it is also proved by the democratic republic in Germany, headed by the Social Democratic government; it is proved by Albert Thomas' attitude towards his (French) bourgeois government. It is proved by the analogous experience in Great Britain and the United States.[8]

Social democracy continued to be the preferred policy of imperialism, their main instrument to keep the working class from power, until the last decades of the 20th century. Then with the final collapse of the Soviet Union and People's Democracies, the flow of revolution turned to retreat, and neo-liberal globalisation became the order of the day throughout the imperialist system of states. Neo-liberalism has been accompanied inevitably by the unbroken ravages of imperialist wars of conquest and intervention, which continue unabated to this day. Death, destruction, displacement of millions, continue to be visited upon the world's peoples. And, as always, the world's peoples desire peace.

Looking back at the First World War, there is no doubt that the Bolsheviks' seizure of power in Russia and their immediate withdrawal from the war was a major factor in bringing peace, in bringing the war to an end. Theirs truly was an anti-war government. Lenin's continued rejection of all opportunist policies was true to the cause of peace.

In today's circumstances and appropriate to today's conditions, the guarantee of peace is the empowerment of the working class, for the working class to constitute itself the nation, opening the path to a new society and taking steps to establish a political process that brings into being an anti-war government. This is the problem to be solved.

Notes

1. William Z Foster, History of the Three Internationals (International Publishers: New York, 1955), p. 225

2. Ibid., p. 207

3. Ralph Fox, The Class Struggle in Britain, Part II: 1914-1923 (Martin Lawrence: London, 1933), Chapter 2

4. Ibid., p. 16

5. Foster, p. 278

6. The Étaples mutiny was a series of revolts in 1917 by British Empire soldiers in France during the First World War.

On August 28, 1916, a member of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), Private Alexander Little (10th Battalion; no. 3254), verbally abused a British non-commissioned officer after water was cut off while he was having a shower. As he was being taken to the punishment compound, Little resisted and was assisted and released by other members of the AIF and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). Four of these men, including Little, were later identified, court-martialled, convicted of mutiny and sentenced to death. Three had their sentence commuted. While the military regulations of the AIF prevented the imposition of capital punishment on its personnel, that was not the case for the NZEF. Private Jack Braithwaite, an Australian serving with the NZEF, in the 2nd Battalion of the Otago Regiment, was considered to be a repeat offender - his sentence was confirmed by General Douglas Haig and he was shot by a firing squad on October 29.

After this incident, relations between personnel and authorities at the camp continued to deteriorate. Mass protests of 1,000 men broke out between September 9-12, until reinforcements of 400 officers and men of the Honourable Artillery Company arrived.

Many men were charged with various military offences and Corporal Jesse Robert Short of the Northumberland Fusiliers was condemned to death for attempted mutiny. He was found guilty of encouraging his men to put down their weapons and attack an officer, Captain E.F. Wilkinson of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Three other soldiers received 10 years' penal servitude. The sentences passed on the remainder involved 10 soldiers being jailed for up to a year's imprisonment with hard labour, 33 were sentenced to between seven and 90 days field punishment and others were fined or reduced in rank. Short was executed by firing squad on October 4, 1917 at Boulogne.

In the 1970s, public interest in the mutinies led to the discovery that all the records of the Étaples Board of Enquiry had long since been destroyed. (Wikipedia)

7. Fox, Chapters 3 and 4

8. Lenin, Selected Works, p.196; quoted in Foster, p. 294

Indian troops headed for East Africa, 1917

Once World War I broke out, Britain called on all its Dominions and colonies for men and materiel. Of these, none bore a greater burden and sacrifice than India. By the end of the war, nearly one-and-a-half million soldiers and non-combatants from India had been brought to the Western Front in Europe and to the other theatres of war. Of these, around 70,000 were killed, and tens of thousands more left shell-shocked, blind, crippled or suffering other severe wounds and mental trauma. India was also bled dry in terms of foodstuffs and other resources for the war effort, with disastrous consequences.

At the outbreak of war, the British Indian Army consisted of 76,953 British, 193,901 Indians and 45,600 non-combatants. It was claimed to be a "volunteer" army. Unlike Britain, there was no conscription in India during the war, though considering the disastrous effect that colonial plunder and exploitation had had on the Indian economy, regular pay and subsistence was an offer many could hardly refuse. It was a disciplined and experienced army. The British only recruited from what they termed "the martial races" from northern India: Pathans, Baluchis, Punjabi Muslims and Sikhs, Nepalese and others. No lower castes were recruited as soldiers, while thousands were employed for cleaning and other menial tasks. No Indians could become commissioned officers, only junior officers of the regiment, while even the most senior Indian officer was subordinate to the most junior British officer. Loyalty was primarily to the regiment, which functioned very much as a "family", the expression being "loyalty to the salt", to the provider. Regiments were organised on common regional, religious and linguistic lines, with many soldiers coming from the same villages. The British were ever-mindful of the lessons of 1857, when disaffection in the Indian Army was one factor which led to the First War of Independence.

Western Front

The first Indian troop ships arrived at Marseilles on September 26, 1914. They were warmly received by the local population. By early October two divisions of the Indian Army were encamped in France. Within just a few weeks they were moved north to the Western Front. Though winter was setting in, they did not have adequate clothing. They remained in their thin cotton khaki drill and sweaters which provided no protection from the wind, sleet and rain of the dark October and November months. In fact it was New Year before they were issued with greatcoats, by which time many had died from cold and frostbite. Initially it had been considered that the Indian troops would be used as reserve or garrison troops, but in fact they were sent straight into the front lines.

Initial enthusiasm soon gave way to despair. The conditions in the trenches were appalling. As well as the bombing and incessant shelling, rains brought flooding. Disease was rife. Trenches collapsed. Frostbite was common. Letters home captured the situation. A Pathan soldier wrote: "No one who has ever seen the war will forget it to their last day. Just like a turnip cut into pieces, so a man is blown to bits by the explosion of a shell.... All those who came with me have all ceased to exist.... There is no knowing who will win. In taking a hundred yards of trench, it is like the destruction of the world."

If soldiers were injured, they would be sent to the hospitals and convalescent depots in France. Once recovered, they would be returned to the front line. A wounded soldier wrote home: "I have no hope of surviving, as the war is very severe. The wounds get better in a fortnight and then one is sent back to the trenches.... The whole world is being sacrificed and there is no cession. It is not a war but a Mahabharat, the world is being destroyed."

Members of British West Indian Regiment stacking shells,

Ypres, France, 1917

Despair was compounded by the fact that, while British soldiers were given regular home leave, no leave was ever given to the Indian troops. This was constantly asked for but refused.

This despair was noted with concern by the British authorities. Ever wary of disaffection, they had taken great care, for instance, to provide separate cooking facilities and water supplies according to the various religious obligations, as well as other measures. Strict censorship of letters home was imposed. Many letters were stopped altogether. In addition great vigilance was shown by the authorities in preventing what they termed "seditious literature" reaching the troops. So concerned were they, for example, about literature from the Ghadar Party that all mail from San Francisco, Rotterdam and Geneva was closely monitored.

Yet even in such trying circumstances, the Indian troops fought with great bravery. This was shown clearly in the battle to seize a German-held salient at Neuve Chapelle in February 1915. The battle raged over four days of relentless fighting. General Douglas Haig had believed a prolonged attack would produce results in the end, even if it meant taking heavy casualties. Both Indian divisions played a prominent part in the battle. One Indian soldier killed in action was awarded the Victoria Cross. In all 4,233 of the Indian Corps were killed, mainly from the heavy German artillery bombardment. Neuve Chapelle was taken. But in the four days of intense fighting and thousands of casualties, only 1,500 metres was gained. Subsequently Haig's report and numerous books written about the battle, including the British state's History of the Great War,[1] made scant if any mention of the contribution of the Indian troops.

The Battle of Loos in September 1915 was to be one of the last major operations undertaken by the whole Indian Corps on the Western Front. The battle raged for two weeks, yet no gains were made. Casualties were high, with most battalions reduced to fewer than a hundred. At the end of the year, having endured a second winter in the trenches, the bulk of the Indian Corps were moved to other theatres of war - the Middle East, Gallipoli and Africa. In early 1917, further Indian troops were recruited for these theatres, where casualties had been high and reinforcements were urgently needed. The Secretary of State for India had asked the Viceroy to raise no less than an additional 100,000 troops by the Spring of 1918 to fight the Turks. Only the cavalry would remain on the Western Front until 1918, and the sappers and miners until 1919, clearing mines.

In the summer of 1916, Haig amassed over a million soldiers in the Somme for a major onslaught on the German lines. The Indian Cavalry would bear the brunt of the operation. In the first few hours alone British troops and their allies, with the Indians to the front, took nearly 60,000 casualties with 20,000 dead. Despite the casualties, Haig ordered the action to continue. The battle raged until mid-November. The total number of dead was 1.3 million. The allies had advanced six miles. Though reports in the newspapers continued for months, few mentioned the Indian Cavalry.

Hospitals

Great publicity was done by the British authorities regarding the hospitals provided for wounded Indian soldiers in England, the care to observe religious rites, and the amenities provided. It was even claimed that the King of England had handed over one of his palaces, the Brighton Pavilion, for conversion into a hospital. This was a blatant lie, since Brighton Council had been its owners for over 50 years. Nearly 120,000 carefully stage-managed postcards of the hospital were distributed and over 20,000 souvenir booklets sent to India. The reality, however, was otherwise. The Pavilion and other hospitals were surrounded by barbed wire. Kitchener's Hospital, the former Brighton Workhouse, was described in one letter home as "Kitchener's Hospital Jail". No English nurses were allowed to treat the patients, only to carry out supervisory roles. There was no fraternisation. Outside activities were limited and under heavy supervision. Visits to the patients were only allowed with passes and under scrutiny, to guard against what were termed "Indian nationalists". Only those with the most severe injuries were returned to India. The others were sent back to the front. Self-harm and suicide were common. Letters home revealed many complaints about the food and the treatment. Many expressed the suspicion that the Indians were being sacrificed as "cannon fodder". Some urged their relatives at home: "Do not enlist!"

Massacre

Indian troops in France in 1915

The war was brought to a close with the Armistice of November 11, 1918, the October Revolution in Russia the previous year being a major factor in bringing peace. The Peace Conference convened in Paris in January 1919, was to last six months, and conclude with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. India had three delegates at the Conference, the Secretary of State for India, Edward Montagu, the Maharaja of Bikaner and Lord Sinha. All three shared a vision of India eventually governing itself, but within the British Empire, with Sinha commenting that Britain must remain "the paramount power".

Back in India the intellectual elite had backed the war expecting concessions as a reward for the sacrifices made. But they were to be bitterly disappointed. The Government of India Act of 1919 only consolidated colonial rule.

The war had had a devastating effect on India. Crops had failed, prices were high and a spirit of unrest was growing. Famine had been declared in Central India. The greatest unrest was in the Punjab. Severe hardship was occurring in the cities. There was great anger at the seizure of foodstuffs for the war effort under the Defence of the Realm Act. War weariness gripped the region, which had sent the most combatants to the front. Villages were mourning the dead and tending the wounded.

The response of the British Government was the Rowlatt Act, passed in London in March 1919. It banned public meetings and muzzled the press. It authorised in camera trials without jury. Persons suspected of revolutionary activity were imprisoned without trial for up to two years. Protests were put down by troops with lethal force.

On April 11, 1919, General Reginald Dyer occupied Amritsar, imposing a curfew and banning all gatherings. A proclamation to that effect was read out on April 13. That day was the festival of Baisaki, the Sikh New Year. Crowds had gathered at the Golden Temple in a festive mood. Nearby was the enclosed park called Jallianwala Bagh. Thousands had gathered there peacefully at a rally to discuss the Rowlatt Act and recent police killings. As is now well known, Dyer brought armed troops in through the single narrow entrance to the park and opened fire on the crowd, ordering his troops to keep firing until their ammunition was exhausted. There was no escape. Around 1,000 were killed and some 1,500 wounded.

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre shocked and enraged the country. Barely five months from the end of the war, in which 400,000 Punjabis had fought, this was Britain's reward. Dyer was unrepentant. The massacre was followed by the bombing of Punjab cities, the extension of martial law and further repression. In London, the report to the War Cabinet for that week barely mentioned the event, simply stating that there had been "trouble" at Amritsar where "troops were called in to restore order". No mention was made of the killings. It was not raised at the Peace Conference in Paris either.

The troop ships returned to Bombay and Karachi. Bands played but there was no heroes' welcome. Too many had died. Too many were crippled, blind or shell-shocked. Some hospitals for the wounded and limbless were set up, but of little help to those returning to remote regions. Crops had failed. Unrest was rife. A new mood of nationalism was growing in the country. The heroes would now be of the Independence or Freedom Movement. In the British official histories of the war there would be little mention of the Indian soldiers who had made such sacrifice.

Note

1. The reference is to the 109 volumes known as History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Committee of Imperial Defence, abbreviated to History of the Great War or British Official History.

(Shrabani Basu. "For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front, 1914-18." London: Bloomsbury, 2015.)

Lenin, April 1917

Brothers, soldiers!

V.I.Lenin, 1914

We are all worn out by this frightful war, which has cost millions of lives, crippled millions of people and caused untold misery, ruin, and starvation.

And more and more people are beginning to ask themselves: What started this war, what is it being waged for?

Every day it is becoming clearer to us, the workers and peasants, who bear the brunt of the war, that it was started and is being waged by the capitalists of all countries for the sake of the capitalists' interests, for the sake of world supremacy, for the sake of markets for the manufacturers, factory owners and bankers, for the sake of plundering the weak nationalities. They are carving up colonies and seizing territories in the Balkans and in Turkey - and for this the European peoples must be ruined, for this we must die, for this we must witness the ruin, starvation and death of our families.

The capitalist class in all countries is deriving colossal, staggering, scandalously high profits from contracts and war supplies, from concessions in annexed countries, and from the rising price of goods. The capitalist class has imposed contribution on all the nations for decades ahead in the shape of high interest on the billions lent in war loans. And we, the workers and peasants, must die, suffer ruin, and starve, must patiently bear all this and strengthen our oppressors, the capitalists, by having the workers of the different countries exterminate each other and feel hatred for each other.

Are we going to continue submissively to bear our yoke, to put up with the war between the capitalist classes? Are we going to let this war drag on by taking the side of our own national governments, our own national bourgeoisies, our own national capitalists, and thereby destroying the international unity of the workers of all countries, of the whole world?

No, brother soldiers, it is time we opened our eyes, it is time we took our fate into our own hands. In all countries popular wrath against the capitalist class, which has drawn the people into the war, is growing, spreading, and gaining strength. Not only in Germany, but even in Britain, which before the war had the reputation of being one of the freest countries, hundreds and hundreds of true friends and representatives of the working class are languishing in prison for having spoken the honest truth against the war and against the capitalists. The [February] revolution in Russia is only the first step of the first revolution; it should be followed and will be followed by others.

The new government in Russia - which has overthrown Nicholas II, who was as bad a crowned brigand as Wilhelm II - is a government of the capitalists. It is waging just as predatory and imperialist a war as the capitalists of Germany, Britain, and other countries. It has endorsed the predatory secret treaties concluded by Nicholas II with the capitalists of Britain, France, and other countries; it is not publishing these treaties for the world to know, just as the German Government is not publishing its secret and equally predatory treaties with Austria, Bulgaria, and so on.

On April 20 the Russian Provisional Government published a Note re-endorsing the old predatory treaties concluded by the tsar and declaring its readiness to fight the war to a victorious finish, thereby arousing the indignation even of those who have hitherto trusted and supported it.

But, in addition to the capitalist government, the Russian revolution has given rise to spontaneous revolutionary organisations representing the vast majority of the workers and peasants, namely, the Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies in Petrograd and in the majority of Russia's cities. Most of the soldiers and some of the workers in Russia - like very many workers and soldiers in Germany - still preserve an unreasoning trust in the government of the capitalists and in their empty and lying talk of a peace without annexations, a war of defence, and so on.

But, unlike the capitalists, the workers and poor peasants have no interest in annexations or in protecting the profits of the capitalists. And, therefore, every day, every step taken by the capitalist government, both in Russia and in Germany, will expose the deceit of the capitalists, will expose the fact that as long as capitalist rule lasts there can be no really democratic, non-coercive peace based on a real renunciation of all annexations, i.e., on the liberation of all colonies without exception, of all oppressed, forcibly annexed or underprivileged nationalities without exception, and the war will in all likelihood become still more acute and protracted.

Only if state power in both the, at present, hostile countries, for example, in both Russia and Germany, passes wholly and exclusively into the hands of the revolutionary Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which are really capable of rending the whole mesh of capitalist relations and interests, will the workers of both the belligerent countries acquire confidence in each other and be able to put a speedy end to the war on the basis of a really democratic peace that will really liberate all the nations and nationalities of the world.

Brothers, soldiers!

Let us do everything we can to hasten this, to achieve this aim. Let us not fear sacrifices - any sacrifice for the workers' revolution will be less painful than the sacrifices of war. Every victorious step of the revolution will save hundreds of thousands and millions of people from death, ruin, and starvation.

Peace to the hovels, war on the palaces! Peace to the workers of all countries! Long live the fraternal unity of the revolutionary workers of all countries! Long live socialism!

Central Committee of the R.S.D.L P.

Petrograd Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.

Editorial Board of Pravda

(Lenin Collected Works, Volume 24)

Receive Workers'

Weekly E-mail Edition: It

is free to subscribe to the e-mail edition

We encourage all those who support the work of RCPB(ML) to also support it

financially:

Donate to

RCPB(ML)

Workers' Weekly is the weekly on

line newspaper of the

Revolutionary Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist)

Website:

http://www.rcpbml.org.uk

E-mail:

office@rcpbml.org.uk

170, Wandsworth Road, London, SW8 2LA.

Phone: 020 7627 0599: