|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 48 Number 22, November 11, 2018 | ARCHIVE | HOME | JBCENTRE | SUBSCRIBE |

Protest by conscientious objectors in Dartmoor in

1917

When the guns fell silent on November 11, 1918, one hundred years ago the world had gone through the most traumatic event in its history which was then called the "Great War" and later to become known as the First World War which had killed millions of people world-wide. If we look today for the role of the British working class in the First World War we are presented only with the suffering of the hundreds of thousands of workers killed and injured in the war with only the humanity and suffering passed down to us by the wonderful poetry writings and art of Wilfred Owen and others. Even the stories of the heroic fight of the conscientious objectors is not well known. The speeches of the ruling elite today continue to distort the predatory imperialist nature of the conflict, waged by Britain and the other big powers to re-divide the world, but also to hide the fact that there was sustained opposition to the war and its consequences, not only in Britain but also in many other countries, in which the working class played a leading role both at home and in the colonies.

Workers' Opposition

In fact, the British working class and the peoples of Britain's colonies were in opposition to the war from the outset and wanted to be free from exploitation and oppression and wanted to be in control of their own nations and to live in peace. Prior to the war huge struggles of hundreds of thousands of workers had broken out. From 1910 to 1914 the dockers, engineering workers, railway workers and miners launched huge strike struggles in what was described at the time as the "General Spirit of Revolt" against the low wages and terrible conditions that workers faced. The historic year of 1913 witnessed the General Strike in Dublin in August and September. The Irish Transport and General Workers Union was under the leadership of James Connolly and Jim Larkin. This fierce struggle of 80,000 Dublin workers aroused an extraordinary response. Solidarity was symbolised in the enthusiastic dispatch through the Co-operative Movement of a food ship to Dublin, and in the sympathetic strikes in which some 7,000 British railwaymen took part. There was a wave of unlimited police terror launched against the Dublin strikers. Two workers were killed, 400 wounded and over 200 were arrested. There was outrage and talk of arming the workers, general strikes and revolutionary action throughout the trade unions.

John Maclean's speech from the dock at his trial for

sedition, May 9, 1918

The summer of 1914 was working up towards an outburst of gigantic workers' struggles for their rights. The miners were preparing new autumn claims. The transport workers were organising and railwaymen and engineers were preparing. In 1914 an alliance for mutual aid was proposed and agreed between the Miners Federation, the National Union of Railwaymen and the Transport Workers Federation. This was to be called the Triple Alliance. The ruling class were in a deep crisis; the problems in Ireland and the internal situation were grave. The English aristocrats, Tory politicians and army officers were preparing for civil war. Lloyd George said openly that with labour "insurrection" and the Irish crisis coinciding, "the situation will be the gravest with which any government has had to deal for centuries". They thought that if the war did not materialise quickly it could be forestalled by the workers seizing power themselves and demanding peace. For the British ruling class, bringing forward the launching of the inter-imperialist war to seize colonies off their rivals in Africa and Asia was imperative to divert the interests of the workers to pursue their war in rivalry with Germany.

However, as soon as the war was declared at this time, the working class of Britain, Germany and France suffered their worst blow from those labour and trade union leaders who declared their support for the war, saying to workers that they should discard their own interests and those of peace, and fight for "defence of the fatherland". These leaders directly assisted the government with its aim to crush the workers' struggles, declare strikes and other trade union activities illegal in many industries for the duration of the war, and for the introduction of the draconian Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), which made active opposition to the war a criminal offence. In 1915, leading members of the Labour Party joined the warmongering coalition government. European socialist parties of the Second International had sunk to the ignominious level of supporting their own imperialist powers in the slaughter of the First World War.

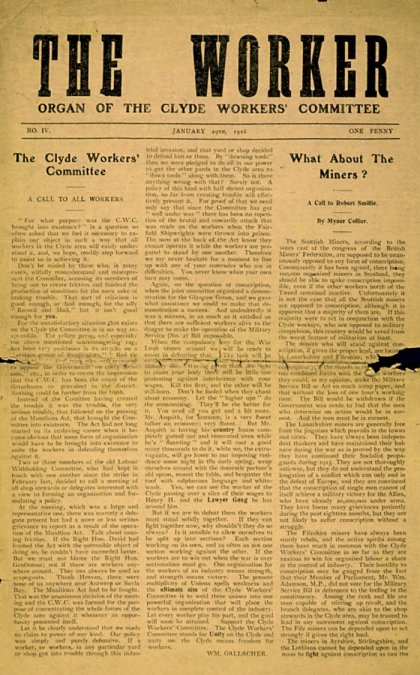

Issue of The Worker, January 29, 1916, newspaper of the

Clyde Workers' Committee

In Britain, opposition to the war and the government's policy of forced conscription was widespread. This was seen with the brave stand of the working class and people against the war. There were 16,000 officially declared "conscientious objectors", who refused to join the armed forces on principle and several thousand of them were imprisoned for their stand.

Also, the working class including the women, who were drafted into the war industries and munitions factories, defied the trade union leaders who supported the war machine and built their own shop stewards committees and transformed themselves into workers' representatives and leaders against the war and its attacks on the workers. Strikes took place during the war against the wishes of the union executives. In 1915 on Clydeside, shop stewards in engineering led the action of 10,000 workers for a pay increase and 15 establishments were involved, including large armament firms, and overtime ceased on war contracts. A ballot on March 9 led to shops coming out on strike. Local shop stewards organised what became the Clyde Workers' Committee, with hundreds of delegates elected directly from the workplace meeting on a weekly basis. Thousands of workers in South Wales also took strike action against repressive government legislation aimed at curtailing their rights The government intervened under the Munitions Act but 200,000 miners struck and in less than one week the government turned about, over-rode the coal owners, and conceded the main points at issue.

The Irish workers had raised the slogan, "We serve neither King nor Kaiser, but Ireland." In 1916, the heroic Easter Rising took place in Dublin led by James Connolly and other Irish leaders for Irish independence against British colonial occupation from which thousands of Irish workers had been led to their slaughter in France. Even though the rising was suppressed and their leaders murdered by the British state, the Rising was an heroic blow against the British warmongering state and changed the face of Ireland for ever.

Citizen Army banner at Liberty Hall, Dublin, declaring

"We serve neither King nor Kaiser but Ireland"

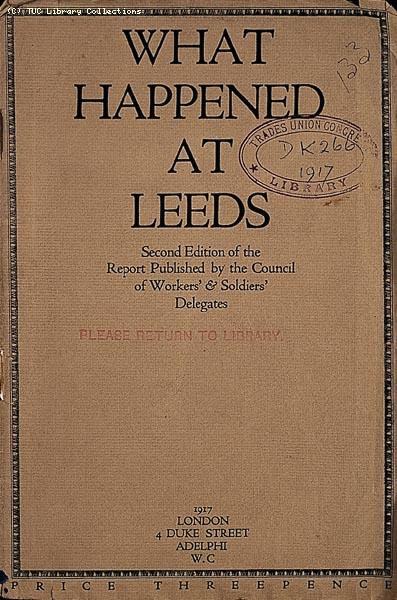

In 1917, engineering workers throughout Britain went on strike in opposition to government plans for more widespread military service and other anti-worker measures. In fact the Russian Revolution which was developing at that time in the overthrow of the Tsar in February which showed the prominence to the Soviets of workers and soldiers in that revolution had a politicising effect on the British working class in opposing the war. This was reflected in the Leeds Convention of June 3, which was attended by 1,150 delegates for the setting up of a Council of Workers' and Soldiers' Delegates. Amongst the calls at the convention were appeals for a struggle against the war. With the completion of the October Revolution in Russia and Russia's withdrawal from the war very large mass scale struggles broke out in the army against the war in the British, French and German armies amongst the soldiers and sailors, armies in which thousands of soldiers had been drafted from the colonies.

At Étaples and Boulogne, between September and December 1917, demonstrations and strikes by troops in protest at their appalling mistreatment by the military commanders resulted in scores of Chinese and Egyptian soldiers in the British Expeditionary Forces being shot and wounded after they refused to work and tried to break out of camp.

There was widespread opposition to the war when rebellion erupted in 1918 when a total of 676 troops were officially court-martialled and sentenced to death for acts of "sedition and mutiny". Though not all these death sentences were carried out, unofficially many other rebellious soldiers were summarily shot on the spot.

The first of the big mutinies on the British mainland occurred in early 1918 when machine-gunners in the Guards staged a mass strike at Pirbright in Sussex. For three days, all soldiers refused duty and instead organised their own voluntary training sessions.

At the end of the year, the spate of rebellions accelerated. On November 13, there was mutiny at Shoreham when troops marched out of base camp in protest at brutality and degrading treatment by their officers. They won. The army responded by demobbing a thousand soldiers the following morning and another thousand each week thereafter.

Leeds Convention to end the war and establish workers'

and soldiers' councils

Among overseas troops, the fervour of dissent was equally pronounced. At Le Havre, Royal Artillery units rioted on December 9, 1918, burning down several army depots in the course of the night. The most sustained mutiny by troops took place at army camps surrounding Calais. Unrest within the units stationed there had been building up for several months beforehand over issues such as cruel and humiliating punishments, the censorship of news from home, and bad working conditions in the Valdelièvre workshops.

There was also discontent over the savage ten-year sentences imposed on five teenage soldiers for relatively minor breaches of discipline, and the harsh regime in Les Attaques military prison, where detained soldiers were flogged and manacled for trivial offences such as talking to each other and were only issued with a single blanket, even during the severest of winters.

Previously, on August 2, 1917, when British troops took up their new positions at Ypres, rebellion broke out on the German battleship Prinzregent Luitpold at the port of Wilhelmshaven. At that point a stoker, Albin Kobis, led four hundred sailors into the town and addressed them with the call: "Down with the war! We no longer want to fight this war!" After returning to the ship some 75 of them were arrested and imprisoned and the leaders were subsequently tried, convicted and executed. "I die with a curse on the German-militarist state," Albin Kobis wrote to his parents before he was shot by an army firing squad at Cologne. He is now remembered as an anti-war hero of the German working class and people.

On October 28, tens of thousands of sailors in the German High Seas Fleet steadfastly refused to obey an order from the German Admiralty to go to sea to launch one final attack on the British navy. By October 30, the resistance had engulfed the German naval base at Kiel, where sailors and industrial workers alike took part in opposing the war; within a week, it had spread across the country, with revolts in Hamburg, Bremen and Lubeck on November 4 and 5 and in Munich two days later. This time the Kaiser's government collapsed setting in motion a course of events that culminated with the Kaiser's abdication and the proclamation of the Weimar Republic in Berlin on November 9, and the signing of the Armistice two days later on November 11, 1918. Far from the victory that that British and its allied powers claimed, this whole catastrophic and unprecedented world war had been brought to an end by the working class and people and their heroic struggles worldwide for peace. However, the struggle of the workers against war were not over. Following the war, attempts took place to by Britain, Germany, Poland and others powers to invade the new Soviet Union to crush the new socialist state. It was in no small part due to the the British workers and the Hands off Russia Committees that Britain intervention in Russia failed and they failed to crush the first new anti-war government.

Imprisonment

As recounted on the website of the Peace Pledge Union, "The Men Who Said No", many conscientious objectors (COs) ended up in prison. For some, this was a conscious choice made at the start of conscription to refuse participation in any activity they felt would contribute to the British war effort, whether in the Non-Combatant Corps or in the various Home Office Schemes. They were known as the Absolutists. For others, imprisonment was the ultimate destination they reached as their thinking developed and they considered what stand to take to be effective in opposing the war and conscription. Still others were imprisoned because the army had violated their right to participate in the military in non-combat roles and they had been court-martialled for refusing orders.

The Wakefield Experiment was one of the last, and shortest-lived, attempts made by the government to encourage Absolutist COs to compromise on their principles. It underscored the harsh treatment of the COs and the violation of their rights, and the unjust nature of Britain's participation in the war as a whole.

The Wakefield Experiment was devised to prolong the imprisonment of COs, and rapidly became a political embarrassment for the government as the war wound to a close. It had been planned as a way to involve COs in their own punishment, allowing them to essentially manage their conditions in prison, and therefore keep them locked up without significant protest until the government saw fit to release them. Though a significant compromise on the part of the government, its purpose was merely to be a stop-gap measure intended to mollify many of the concerns and protests that had built up over the past two years.

A group of Conscientious Objectors leaving Dartmoor

Prison

After a period of settling in, the Wakefield men had taken it upon themselves to organise and run the prison as they wished. Committees divided the labour of prison upkeep and cordially invited the wardens to help if they wished. The Governor, with no instructions on what to do, allowed the Chairman of the Committee, Walter Ayles, to represent the official Home Office plan for the prison to the assembled men. Ayles presented the rules and regulations on how COs in Wakefield would be expected to work and live on September 16. There had been no great threat of exceptional mass punishment, simply that if the rules of the new scheme were not followed, men would be returned to prison. The position was simple. In exchange for their work, COs would stay in Wakefield and be managed, in all essential respects, by themselves.

Two days later, with a resounding rejection of the principle of compromising conscience for better conditions, all but six of the 125 COs were back in locked cells, soon to be returned to the prisons they came from.

The final piece was the creation of the "Manifesto of the Absolutists

at Wakefield." Not only had the COs held there organised and discussed

their thoughts, but had formed a committee which wrote, drafted and distributed

a clear statement of intent. The Manifesto signalled the clearest statement of

the Absolutist

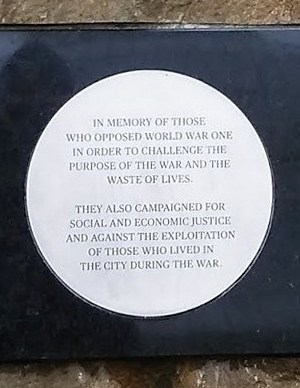

Plaques to conscientious objectors in

Glasgowposition. Despite better conditions, no manner of

compromise would fulfil the aim of the Absolutists: unconditional liberty and

discharge from the army. The Manifesto explained that the government "take

for granted that any safe or easy conditions can meet the imperative demands of

our conscience. No offer of schemes or concessions can do this. We stand for

the inviolable rights of conscience in the affairs of life."

The 123 men at Wakefield refused any form of compromise with the government and demanded either release, or a return to prison. No change in their circumstances could win them over and put them to work.

The position outlined in the Manifesto had been the Absolutist stance since before conscription had become law, and the rejection of the Wakefield Experiment was the last attempt by the government to subvert or undermine it. The Wakefield men returned to prison, and the incarceration of COs continued as before.

Conclusion

The experience of the First World War showed that the workers of Britain and other countries must play a leading role in society to stop the war. The betrayal by the Labour Party and other parties which comprised the Second International showed that the workers must organise themselves based on their own independent programme and aims. They must give up illusions that electoral parties which comprise party governments in the service of the bourgeoisie will serve their interests.

Today, the workers must organise with the perspective of creating their own anti-war government, building the proletarian front to bring this about, and settling scores with all pretexts for the betrayal of their interests.