|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume 48 Number 22, November 11, 2018 | ARCHIVE | HOME | JBCENTRE | SUBSCRIBE |

Chris Coleman

Stuttgart Congress of the Second International,

1907

The treachery of the social-democratic parties which comprised the Second International was, in the words of one commentator, "the worst debacle ever sustained by the world's working class in its entire history".[1] In the quest to lead the working class to constitute the nation today and fight for anti-war governments, the experience of the international workers' movement in defeating the social chauvinism of the Second International has important lessons.

For nigh on 25 years, beginning at the Brussels conference of 1891, the Second International had been passing resolutions warning of the war threat and calling for opposition to inter-imperialist war. The London conference of 1896 had even called for the abolition of standing armies, arming the people, arbitration courts and war referendums by the people. At the Stuttgart Conference of 1907 the famous resolution was passed, its concluding paragraph drafted by V.I. Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, the principles of which remain valid to this day. It read:

If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working class and of its parliamentary representatives in the country involved, supported by the consolidating activity of the International (Socialist) Bureau, to exert every effort to prevent the outbreak of war by means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the accentuation of the class struggle and of the general political situation.

Should war break out nonetheless, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and to do all in their power to utilise the economic and political crisis caused by the war to rouse the peoples and thereby hasten the abolition of capitalist class rule.[2]

There is little doubt that the social democratic parties could have prevented the war or at least brought about its speedy termination. In a situation of mass opposition to war throughout Europe, the most powerful of the parties of the Second International, the German Social Democrats, were in a position to do so, and moreover, even to lead a revolution. Only the Russian Bolsheviks, however, of those in any position to do so, remained true to the principles agreed at Stuttgart. And it was to be the October Revolution, led by them, which brought the terrible destruction of the war to an end. But as the dark clouds of war gathered and every imperialist power found justification and saw opportunity to advance its interests - Germany to seize colonies from Britain and France and the Ukraine, the Baltic provinces and Poland from Russia; tsarist Russia to partition Turkey and seize Constantinople and the straits to the Mediterranean; Britain to smash its rival Germany and seize Mesopotamia and Palestine from Turkey; France to seize the Saar and Alsace-Lorraine from Germany; and the USA in the background ready to exploit any opportunity to advance its ambition for world mastery - party after party of social democracy took up the capitalist's banner of national chauvinism and supported war. Only the Russian and Serbian parties in the Second International resisted.

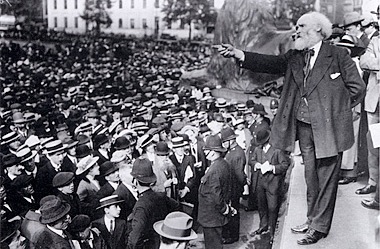

Independent Labour Party MP James Keir Hardie speaking in

Trafalgar Square August 3, 1914, opposing the outbreak of war

Decisively, the German Social Democrats were among the first to move, voting for war credits in the Reichstag. In Britain, typically, the social democrats were more circumspect. The mass of the working class in Britain, as in other countries, was bitterly opposed to the war which broke out in August 1914. The Labour Party responded to this sentiment by calling demonstrations throughout the country on the eve of Britain's entry. The British section of the International Socialist Bureau issued an anti-war manifesto, signed by Arthur Henderson and James Keir Hardie, which ended with the slogans "Down with Class Rule", "Down with War". These two were chief speakers at an enormous Trafalgar Square rally, the biggest ever known, where resolutions were passed calling upon the organisations of the workers to keep to the resolutions of the Second International against imperialist war. Other huge demonstrations took place across the country.

However, the Labour Party leaders ensured things did not go beyond demonstrations and fine words. In the very first days of August the Daily Citizen, organ of the Trades Union Congress and Labour Party, called on the workers to "stand together in defence of the Motherland". Within weeks the trade unions signed a pact of "civil peace" with the Liberal Government, the Labour Party entering into a similar pact in the political field. The Independent Labour Party (ILP), whose leaders including Ramsay Macdonald were also leaders of the Labour Party, issued "Down with the War" manifestos, but these were confined to demands for "peace" and calling on the workers to do "general propaganda for socialism, though not dealing specifically with the war". Meanwhile rank-and-file militants of the ILP and British Socialist Party were encouraged to take up pacifism and conscientious objection, subject to the brutal criminalisation of conscience by the British elite.

Lenin's work "The Collapse of the Second

International" from the Red Clyde collection

By the end of August the National Labour Party executive and the Parliamentary Labour Party, which included five ILP members, had accepted an invitation from the Government to join the recruiting campaign. Such treachery was closely followed by an agreement between Henderson and Prime Minister Lloyd George which prohibited strikes and adopted compulsory arbitration for any disputes in munitions production. This agreement led to the draconian Munitions Act of June 1915, which enforced compulsory arbitration throughout industry and controlled the employment and movement of all workers. Local Munitions Tribunals, including trade union officials, enforced its strictures. By early 1916, when compulsory conscription was introduced, Labour Party leaders were part of the Government and had ceased any form of opposition to the war.[3]

"Defence of the rights of small nations" was one of the pretexts of the British government for entry into the war. But when the Irish rose on Easter 1916 and declared the Republic, the uprising was crushed with great brutality, mass executions and other atrocities. Labour leaders, now Ministers in the government, were complicit in this. The ILP in their journal Labour Leader declared that they "condemn as strongly as anyone those immediately responsible for the revolt" and said that James Connolly, cruelly murdered by the British while critically wounded, was "terribly and criminally mistaken".[4]

Support for the inter-imperialist war by the social democrats, however, was only the beginning of the great betrayal. Despite the dreadful slaughter and destruction of the war, it opened up great opportunities for the advance of the people's cause. Four great Empires had been destroyed - the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman. New independent nations came into existence. Revolutionary upheavals with a distinct anti-capitalist socialist character swept Europe. But only the Bolsheviks in Russia were to seize the opportunity. Elsewhere the treachery of social democracy was to be the main factor in revolution and socialism not prevailing in most if not all the area involved.

In Germany itself revolution broke out in November 1918, sparked by the Kiel mutiny in the German Navy. Revolt spread like wildfire and, influenced by the Bolshevik example, Soviets were established all over the country. On November 9 the national government collapsed and the Kaiser fled. With leadership, the German working class was in a position to push through the proletarian socialist revolution. The Social Democratic leadership had no such intention. They did not want or believe in socialism. They were liberals, who only strove to patch up capitalism a bit here and there. Their leader, Ebert, had said: "I hate revolution as I hate sin."[5] In close co-operation with the capitalists "to save Germany from Bolshevism", they set up first a caretaker government headed by Ebert, then a Provisional Government of Social Democrats and Independents. They manipulated the German Soviet's Congress to support the Provisional Government, then provoked armed struggle with the Spartacists and set reactionary military elements against the fighting workers. Berlin's streets ran with blood and the rebellion was crushed. In the course of this Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were arrested and murdered.

Within weeks the bourgeois Weimar republic was set up, with the capitalists cynically putting right-wing Social Democrats at the head of the government - Ebert himself, Scheidemann and Noske. Even the Soviets were given "advisory" capacity! It was this government, headed by Social Democrats, that signed the Versailles Treaty which was inevitably to pave the way for the rise of fascism and the horrors of the next world war.

By the end of World War I, a revolutionary situation had developed in Britain too. Unofficial strikes had become widespread. The Shop Stewards Movement, severed from "official" Labour, grew in influence. In Scotland, the revolutionary Clyde Workers Committee, despite all attempts to crush it - including the repeated jailing and brutal mistreatment of its political leader, the teacher John MacLean - had made laws regulating employment and conscription inoperable on the Clyde, among other victories. A huge movement had developed against the war. Mutinies spread in the Army and Navy - notably the burning of the base at Étaples by mutineers.[6] Even the police had formed a union and were striking. Mass support for the Bolsheviks was recorded among the militant workers and when the government sent troops to intervene in the new Soviet state, disaffection among the soldiers and sailors was a major factor in bringing the intervention to a sorry end. When again the government sought to intervene in support of the Polish White Guard invasion of Soviet Russia in Spring 1920, mass action in opposition took place throughout the country. The munitions ship Jolly George, bound for Poland, was famously rendered unsailable by the dockers on the Thames. "Councils of Action" were set up by workers across the country. Lenin himself likened the situation in Britain to that in Russia at the time of the February Revolution of 1917, saying that the Councils of Action were in essence Soviets, and pointing out that even the opportunist social democrats had been forced to support them.

Once again, however, these same social democrats were to rescue the bourgeoisie. Vicious anti-Soviet propaganda and attacks on the revolutionary workers, as well as on the newly formed Communist Party, rapidly became the official policy of the Labour Party and ILP. This treachery, combined with the heritage of opportunism even among the best elements of the working class, and the relative weakness and frequent sectarianism of the communists, meant that the bourgeoisie survived the revolutionary crisis of 1919-20 in Britain.[7]

The key role of the opportunist social democrats in preventing socialist revolution and keeping the capitalists and imperialists in power in all but Russia, when the opportunity had so vividly presented itself during the First World War period, was summed up brilliantly by Lenin at the Second Congress of the new Communist International (the Third International) in 1920. He famously said in his report:

Practice has shown that the active people in the working class movement who adhere to the opportunist trend are better defenders of the bourgeoisie, than the bourgeoisie itself. Without their leadership of the workers, the bourgeoisie could not have remained in power. This is not only proved by the history of the Kerensky regime in Russia; it is also proved by the democratic republic in Germany, headed by the Social Democratic government; it is proved by Albert Thomas' attitude towards his (French) bourgeois government. It is proved by the analogous experience in Great Britain and the United States.[8]

Social democracy continued to be the preferred policy of imperialism, their main instrument to keep the working class from power, until the last decades of the 20th century. Then with the final collapse of the Soviet Union and Peoples' Democracies, the flow of revolution turned to retreat, and neo-liberal globalisation became the order of the day throughout the imperialist system of states. Neo-liberalism has been accompanied inevitably by the unbroken ravages of imperialist wars of conquest and intervention, which continue unabated to this day. Death, destruction, displacement of millions, continue to be visited upon the world's peoples. And, as always, the world's peoples desire peace.

Looking back at the First World War, there is no doubt that the Bolsheviks' seizure of power in Russia and their immediate withdrawal from the war was a major factor in bringing peace, in bringing the war to an end. Theirs truly was an anti-war government. Lenin's continued rejection of all opportunist policies was true to the cause of peace.

In today's circumstances and appropriate to today's conditions, the guarantee of peace is the empowerment of the working class, for the working class to constitute itself the nation, opening the path to a new society and taking steps to establish a political process that brings into being an anti-war government. This is the problem to be solved.

Notes

1. William Z Foster, History of the Three Internationals (International Publishers: New York, 1955), p. 225

2. Ibid., p. 207

3. Ralph Fox, The Class Struggle in Britain, Part II: 1914-1923 (Martin Lawrence: London, 1933), Chapter 2

4. Ibid., p. 16

5. Foster, p. 278

6. The Étaples mutiny was a series of revolts in 1917 by British Empire soldiers in France during the First World War.

On August 28, 1916, a member of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), Private Alexander Little (10th Battalion; no. 3254), verbally abused a British non-commissioned officer after water was cut off while he was having a shower. As he was being taken to the punishment compound, Little resisted and was assisted and released by other members of the AIF and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF). Four of these men, including Little, were later identified, court-martialled, convicted of mutiny and sentenced to death. Three had their sentence commuted. While the military regulations of the AIF prevented the imposition of capital punishment on its personnel, that was not the case for the NZEF. Private Jack Braithwaite, an Australian serving with the NZEF, in the 2nd Battalion of the Otago Regiment, was considered to be a repeat offender - his sentence was confirmed by General Douglas Haig and he was shot by a firing squad on October 29.

After this incident, relations between personnel and authorities at the camp continued to deteriorate. Mass protests of 1,000 men broke out between September 9-12, until reinforcements of 400 officers and men of the Honourable Artillery Company arrived.

Many men were charged with various military offences and Corporal Jesse Robert Short of the Northumberland Fusiliers was condemned to death for attempted mutiny. He was found guilty of encouraging his men to put down their weapons and attack an officer, Captain E.F. Wilkinson of the West Yorkshire Regiment. Three other soldiers received 10 years' penal servitude. The sentences passed on the remainder involved 10 soldiers being jailed for up to a year's imprisonment with hard labour, 33 were sentenced to between seven and 90 days field punishment and others were fined or reduced in rank. Short was executed by firing squad on October 4, 1917 at Boulogne.

In the 1970s, public interest in the mutinies led to the discovery that all the records of the Étaples Board of Enquiry had long since been destroyed. (Wikipedia)

7. Fox, Chapters 3 and 4

8. Lenin, Selected Works, p.196; quoted in Foster, p. 294